We independently review all our recommendations. Purchases made via our links may earn us a commission. Learn more ❯

They’re calling Japan’s premium CD formats the new “green marker” snake oil.

A Deep Purple Machine Head UHQCD costs ¥2,800 ($26) in Japan. A Beach Boys SHM-CD runs ¥5,000 ($46). Standard pressings of the same albums sell for about ¥1,500 (~$14). Both formats cap out at the same Red Book specification that has governed every CD since 1980.

The ceiling is 44.1kHz sampling and 16-bit depth, no matter what the disc is made of. Same ones and zeroes, same output at the DAC.

“Spending extra money on these discs for the better materials would appear to be a waste,” concluded the engineers at Troll Audio after oscilloscope testing.

So why do some of these premium pressings genuinely sound better? The answer has nothing to do with plastic.

Table of Contents

- When a Zero Is Just a Zero

- What Labels Don’t Advertise

- This Happened Before With Green Markers

- Buying the Sleeve, Not the Sound

When a Zero Is Just a Zero

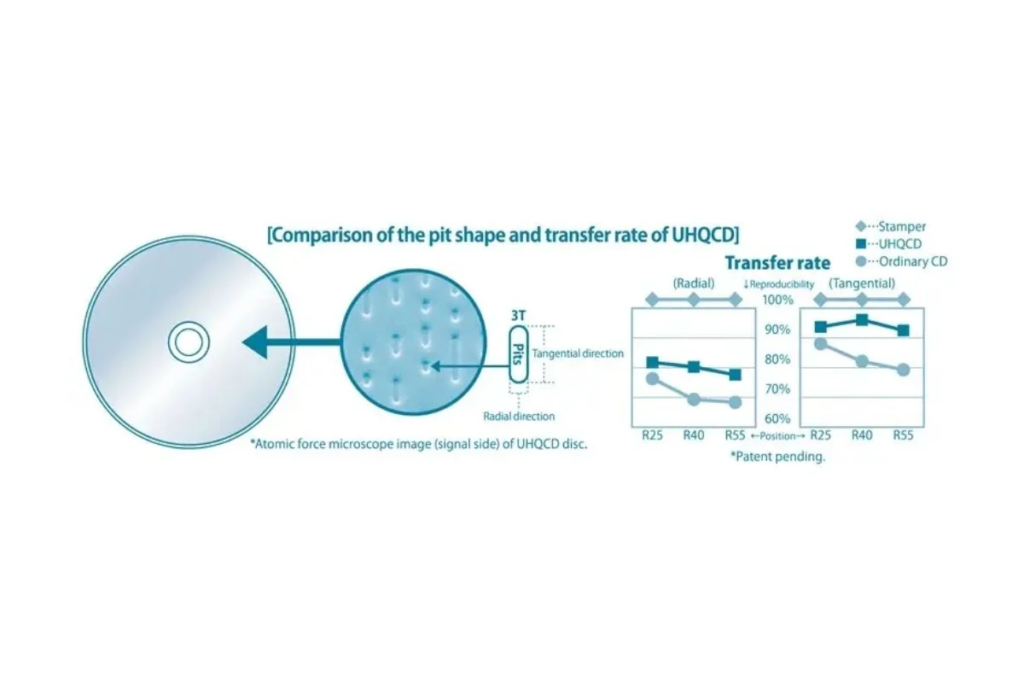

Digital audio stores information as discrete binary values. A 0 is a 0 and a 1 is a 1, regardless of whether the laser reads them off bargain-bin polycarbonate or JVC Kenwood’s proprietary SHM blend. There is no “better reading” of binary data. The disc either delivers the correct bits or it doesn’t.

Troll Audio put this to the test with an oscilloscope, comparing a budget Naxos disc, a premium Deutsche Grammophon pressing, and a UHQCD on a Philips CD150 player chosen specifically for its sensitivity to disc quality.

“The histograms are virtually identical, and none of the images exhibit any feature setting them apart from the others,” the site reported of the DAC clock signal comparison.

Some audiophiles argue entry-level players benefit more from premium discs than high-end systems. Even if marginal jitter differences exist at the transport stage, those differences vanish at the DAC. And anyone buying $30 UHQCDs is unlikely to be spinning them on a $50 player.

Head-Fi users comparing EAC checksums found SHM-CD and standard CD rips produced identical files when the mastering source matched. Mastering engineer Barry Diament, one of the first to cut CDs at Atlantic Records in 1983 with credits including AC/DC and Led Zeppelin, put it bluntly.

“Absolutely no difference between it and a standard CD,” Diament confirmed.

The measurements are settled. But some premium CDs do sound different from their standard counterparts, and the disc itself deserves none of the credit.

What Labels Don’t Advertise

The trick works because labels pair new remasters with premium disc formats. Buyers hear an improvement over their old pressing and credit the polycarbonate. They’re not wrong about the sound. They’re wrong about the source.

Blue Note’s 85th anniversary UHQCDs make the point cleanly. Those discs feature Kevin Gray masters, the same tapes used for the Tone Poet and Classic vinyl reissues. The sound improvement comes from Gray’s remastering, not the disc substrate.

“It’s all about the mastering not the material used to produce the CD,” wrote mikechadwick on PinkFish Media. “The Blue Note 85’s use the Kevin Gray masters that are also used to manufacture the Classic & Tone Poet series.”

Audiophile forums keep reaching this conclusion on their own. “My SHM and Blu Spec CDs don’t sound noticeably better than the standard releases, except where different masters make their differences obvious,” noted Redditor xdamm777.

Labels don’t advertise this conflation. And the willingness to believe in material-level improvements isn’t new. Three decades ago, the same community fell for something even more absurd.

This Happened Before With Green Markers

In 1990, audiophiles became convinced that coloring the edges of their CDs with green felt-tip markers improved sound quality. The theory held that green ink absorbed stray red laser light bouncing inside the disc, allowing cleaner data retrieval.

Companies jumped in. AudioPrism sold purpose-built green pens for $30. Krell, a respected high-end manufacturer, released CD players that bathed the disc tray in green light. Sony studied the phenomenon. The audiophile press gave it serious coverage.

Then Stereophile tested it and found no measurable differences in data retrieval. The green markers quietly disappeared from catalogs.

The parallel to premium CD formats is exact. Green markers and SHM-CDs both claim optical reading improvements that cannot survive measurement.

Both generated commercial products priced for believers. Both tap the same psychological impulse that drives this cycle. But audiophiles want simple, tangible interventions that make expensive systems sound better.

Buying the Sleeve, Not the Sound

“If they are Red Book standard compliant, they are regular CDs as far as your CD Player is concerned. It’s just marketing,” wrote Doomlord_uk on PinkFish Media.

Sometimes a premium Japanese CD includes a genuinely superior remaster. Labels could ship that remaster on a standard disc for half the price. They don’t, because the premium polycarbonate is the story that justifies the markup. The obi strip and the fancy packaging sell the rest.

Diament has been mastering CDs since 1983, when he was one of the first engineers to cut for the format at Atlantic Records. His verdict on premium formats hasn’t changed.

The mastering is what you hear. The plastic is what you pay for.

By Colin Toh