We independently review all our recommendations. Purchases made via our links may earn us a commission. Learn more ❯

A top audio engineer explains why “pro studio” gear can backfire in a quiet living room.

Balanced XLR cables have long been treated like a quick upgrade for cleaner sound. They’re a staple in studios and often marketed as “professional grade,” which makes them feel like the obvious choice for home audio, too.

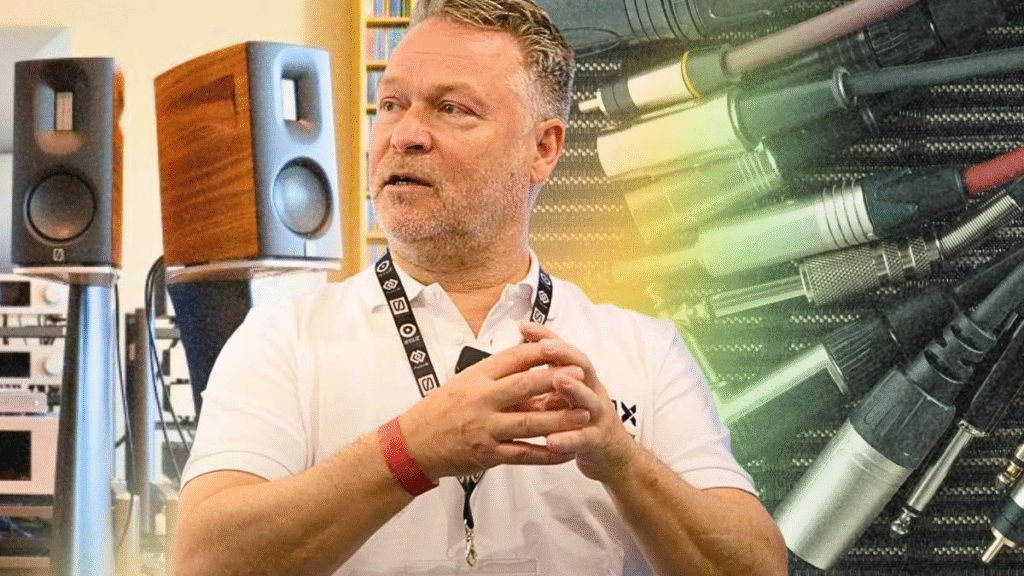

But according Michael Børresen, co-founder and designer at Audio Group Denmark, that belief doesn’t hold up in a living room. In many setups, balanced doesn’t reject noise any better and may even make the system more complicated.

Here’s why that matters and what to do about it.

Table of Contents

So What to Do Next?

Why People Believe in Balanced Cables

Balanced connections send the same signal on two wires, with one inverted. At the receiving end, the device compares the pair and cancels the noise that affected both equally.

This approach was built for studios and live rigs where long cable runs, crowded racks, and lots of gear powered from different circuits. In those environments, interference and crosstalk are real problems, so XLR became the safe default.

That’s why that “pro gear = better” halo followed balanced into home audio. Many listeners assume that if studios use XLR, it must also sound cleaner at home.

But most living rooms don’t have 30-meter snakes or banks of dimmers. You’re usually running one source at a time over short interconnects.

In that context, balanced doesn’t automatically buy you lower noise, as good grounding, shielding, and sensible layout matter more.

So the belief comes from a real benefit… just not the typical home use case.

The Real Source of Noise at Home

In a typical home setup, the biggest contributor to noise isn’t crosstalk between multiple signals, but the contamination on the ground path. This kind of interference happens even when you’re only playing a single source over a short cable run, which is how most home systems are used.

Ground contamination refers to unwanted noise riding on the system’s reference or shield. It can come from switching power supplies, computer peripherals, routers, or small voltage differences between components plugged into different outlets.

And, because both single-ended and balanced cables rely on a ground or shield, any interference introduced here can still couple into the audio signal.

As Michael Børresen explains, this is why balanced connections don’t automatically yield cleaner playback at home.

“Most of the noise bleeding into your signal wires is from the ground side anyway. So if you pollute the ground in a balanced circuit, you still have noise from that. So it doesn’t, it doesn’t give you any real benefits,” he explains in a recent interview with Next Level HiFi.

That’s why layout and grounding often matter more than connector type. That can mean powering the system from the same outlet, keeping interconnects short, separating signal and power cables, moving noisy wall warts, or adding USB isolation when needed. These simple steps usually help more than switching from RCA to XLR.

Børresen’s Case for Simplicity

For Michael Børresen, the choice to favor single-ended signal paths is a deliberate engineering decision. Since he believes most noise in home setups comes from grounding rather than inter-signal bleed, he focuses on keeping circuits as simple as possible.

His view is straightforward: every added amplifier or processing stage has an audible cost in terms of microdetail, scale, and dynamics.

That philosophy starts at the volume control. His preamp uses the line stage itself as a virtual-ground amplifier, setting level via two precision resistors in the feedback loop.

This keeps the signal-to-noise ratio intact at low volumes and lowers distortion as you turn the volume down. And, because the implementation is inherently single-ended, the cleanest path avoids converting to balanced.

To add XLR on gear like this, you’d need extra line-driver/receiver stages, ICs or discrete blocks that, in his view, are the very complexity he’s avoiding.

“So essentially, you do something balanced by using another set of amplifiers, another set of a chip or an op amp. And if you do a discrete op amp, you actually need two to make them balanced so you have a true balanced output.” he explains.

This isn’t a universal rule against balanced, though. If a component is fully differential end-to-end, XLR may be the native, most transparent path.

Still, Børresen’s point is narrower. For him, when a device is designed around a single-ended topology, staying single-ended avoids unnecessary conversions and better preserves the intent and the sound of the original design.

So What to Do Next?

Here’s how to turn all of this into better results at home.

- Match the path to the design: If your component is single-ended internally, use RCA to avoid unnecessary conversion stages. If it’s fully differential, use XLR.

- Clean up your ground: Power everything from the same outlet or conditioner to minimize loops and voltage differences.

- Control physical layout: Use short interconnects, keep signal lines away from power cords, and relocate or replace noisy wall warts.

- Tame computer noise: Add USB isolation or use higher-quality interfaces if needed.

- Save XLR for when it matters: Balanced can help with long cable runs or noisy environments, but it’s not a guaranteed upgrade in quiet living rooms.

Alexandra Plesa